Asmi Musthafa, Programme Assistant (Labour Migration), ILO Colombo

In June 1986, soon after I was born, my father went overseas. I grew up in Maruthamunai, a small coastal village of about 15,000 people in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka. I come from a family of seven and have four siblings – three elder sisters and a younger sister.

We were all very young when my father left the country to work in Saudi Arabia as a driver for a household. I can’t begin to imagine how my mother felt, tasked with looking after five kids without the direct support of her husband.

Migrating for work was not uncommon in our village. Many of my relatives had already gone abroad to work as labourers and domestic workers. Two of my aunties and an uncle also worked in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, so my mother wasn’t too worried. While many in the village worked in the fisheries sector, others migrated to Middle Eastern countries. In the early 1980’s the money they sent back home sustained the village economy, and these remittances were the cornerstone of rural development at that time.

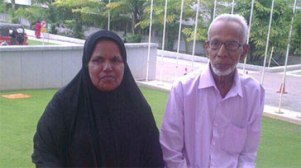

My parents

I still remember how the re-chargeable lamp my father brought for us was a popular fixture used by our entire community. We were plagued with frequent electricity failures in the evenings and our neighbours often borrowed it during emergencies.

I wrote letters to my dad and sometimes we exchanged recorded audio cassettes. Those were times before mobile phones or the internet, and making phone calls was rare because it was very expensive. So, I would record a message on a cassette and post it to him, and he would do the same. At least a month would pass between our voice messages. Relatives hung around the village post office eagerly awaiting the sealed orange mailbag that was delivered by bus. We would wait impatiently until the Postmaster completed the formalities, opened the bag and then called us to collect the letters and parcels addressed to us.

One day, I got a letter with 10 Saudi Riyals (approximately US$ 3.10) sent to me by my dad. I found someone who exchanged it with me for Sri Lankan Rupees. I walked straight to a stall selling spiced cassava chips and had mouthfuls of the savoury, crunchy snack. Back then, it was the most amount of money I had ever had in my pocket.

My father’s job was the only source of income for my family. My mother handled our finances with remarkable efficiency, saving a large amount of the money received. Then, there was no internet banking facility to remit money to Sri Lanka from overseas. All migrant workers depended on snail mail to send cheques home. My father’s monthly income was around 1,000 Saudi Riyals, which was equivalent to 15,000 Sri Lanka Rupees (US$ 310) then. Would you believe that my mother not only managed to pay for our education but she was also able to save money to build four houses for my sisters, to be given to them when they got married, as per local custom. My mum and dad studied only up to Grade 4 and dropped out of school when they were nine, due to poverty. I often wonder how they learnt this level of economic management.

My graduation

Remittances are recognized as the hidden engine of globalization, with 270 million migrants around the world sending home US$ 689 billion, according to the World Bank. Remittances are now the greatest source of foreign capital for developing countries, more than Foreign Direct Investment.

In Sri Lanka, remittances are a major foreign exchange source, contributing immensely to the national economy and forming 10 per cent of the GDP. Hundreds of thousands of Sri Lankans migrate for work to provide a better financial future for their loved ones. Their remittances are invested into self-employment, education, housing and basic family needs. Furthermore, many migrant workers are exposed to other cultures and help to create a global society with diverse worldviews.

Growing up with a father working as a migrant worker and watching my mother judiciously manage the remittances we received, I have often wondered about other Sri Lankans who have migrant worker parents or family members. How did husbands use money sent by their wives working overseas? How did their experiences differ from mine? What are the implications for communities?

My dad worked as a driver continuously for ten years and returned home in 1996. I had remote interactions with my dad and when he returned to stay with us, he was quite a stranger to me then. After he returned, I was able to get to know him all over again. Although it was not very high, our family finances were better than most. Now, looking at my family of well-educated siblings and seeing all of us work to achieve our dreams, I understand how he helped lift up the family by working abroad.

I do not know how I can show my gratitude to my migrant worker father.

The ILO supports a rights-based approach to remittances and works with both migrant workers and financial institutions to maximize the benefits of these financial flows.